By early grade school Booey and I were inseparable. Together we did all the things that little boys did living in the early ’60s, long before the reign of iPhones and Netflix. In those days, your home phone was a black rotary one that was centrally located in the house. It was an adult-only device used primarily to make or receive the occasional call coming from friends or family. The television, if you had one, was strategically located in the living room, where it stayed indefinitely as it took one reasonably strong dad and three uncles to get it there in the first place. The TV, too, was almost exclusively controlled by adults. This made sense because programs like Groucho Marx, To Tell the Truth and Lawrence Welk had zero allure for kids our age. The only exception was Saturday morning cartoons and Sunday evening Disney. Beyond those few sacred hours of entertainment, the things we did for fun were totally of our own making. Should you get caught whining about having nothing to do, you would either find yourself banished to your room to read or, even worse, slapped with extra chores without any promise of increased allowance for your trouble.

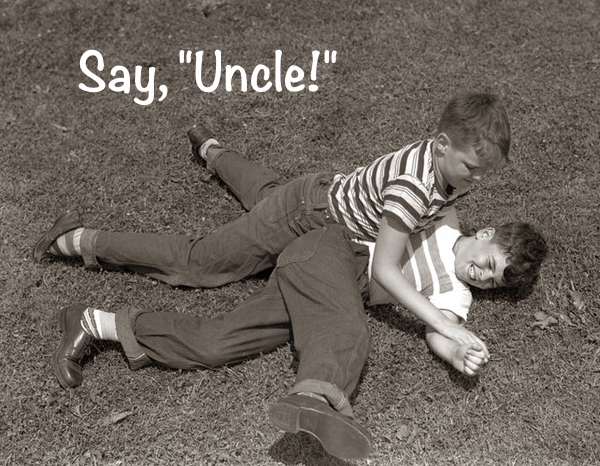

Contrary to what you might think, however, boredom was almost unheard of in those days. Together Booey and I climbed trees, rode bikes, fought wars, had hydroplane races (we lived in Seattle, the home of the Gold Cup Races and Miss Bardahl) and, on the days when other kids joined in, we played wiffle ball in the street or a neighborhood favorite, kick-the-can. No matter the game, we often seemed to wrap things up with a good old-fashioned wrestling match. Somehow it was important to regularly check in to see who was the strongest. Fortunately for our friendship, we turned out to be pretty evenly matched. The important point is that each challenge ended with the begrudging loser being forced to acknowledge defeat by crying “uncle!”.

Spending time wondering how “uncle” became the accepted way to admit defeat ends much like asking how Bruce became Booey. The answer is lost in time. Some say it derived from an old Irish word “anacol,” which means “an act of deliverance or safety,” while others suggest a Latin root. For us, “uncle” was simply the gentleman’s way of allowing your opponent to plead for mercy without actually having to say the word. It’s remarkable that even at our young age, mercy was a word that seemed to stick in your throat. Saying “uncle” was a way you could admit defeat—but only for this round. Asking for mercy, on the other hand, had a certain finality to it. Saying “uncle” was only temporary; asking for mercy meant you had truly come to the end of your rope.

Today, with the stakes much higher, I fear we adults often try to maintain the same subtle distinction. When we find ourselves pinned to the ground by a very bad choice, a runaway addiction, a shattered relationship or an untreatable pandemic, we would much rather say “uncle” than admit we are facing a situation we cannot possibly untangle on our own. Nothing seems to be harder on the human ego than acknowledging that we are helpless. Whether it’s a boyhood wrestling match or a life situation spiraled out of control, the reality is that when you are completely down your options become few. You can keep saying “uncle” in hopes that by some herculean effort you can throw off your opponent, or you can admit your utter defeat and plead for mercy, inviting another to do for you what you could not do for yourself. The first alternative, though momentarily satisfying because it retains the illusion of self-sufficiency, generally comes crashing down in short order. The second alternative, though embarrassing and painful, is often the wisest choice because in reality it represents the only path forward if your desire is to actually get back on your feet again and stay there.

In 2 Corinthians 4:1, Paul is clear about what we need if our desire is to truly stand and help others do the same: “Therefore, since through God’s mercy we have this ministry, we do not lose heart” (2 Cor. 4:1). Paul’s use of the term “ministry” here is not limited to the formal kind of ministry we might think of when we hear that word. He is not talking specifically about pastors or those who might serve us on any given Sunday. He is addressing anyone who has responded in awe to God’s invitation to be reconciled to him. In that moment, when our brokenness comes into contact with his absolute perfection, saying “uncle” would never be enough. Mercy is the only remedy potent enough to rout the disease that permeates our lives down to the bone. In that desperate moment when we cry out “mercy!”, not only are we changed, we also become dispensers of the life we have received and this becomes our ministry. Rather than being crushed under the weight of our own pride and arrogance until we “lose heart,” we are now free to become ministers (a noun) and minister (a verb) the life changing mercy, love and grace we have received.

In my lifetime, I have seen Americans square off against what felt like insurmountable odds and the challenges of previous generations that make mine pale in comparison. Though I am deeply grateful for the amazing heroism and resilience that marks our past, I am equally concerned that as we wade yet again into uncharted waters we might be tempted to only say “uncle.” We readily admit that current circumstances may be beyond our control, but in response we lean into a self-sufficiency that, when pushed too far, can become our Achilles heel. “God resists you when you are proud but continually pours out grace (mercy) when you are humble” (James 4:6 PTP). When it comes to God, whether American, Italian, Iranian or Chinese, may it never be said that in our pride we cried “uncle” when what we really needed to do was cry “mercy.” In Lamentations 3, the writer declares that God’s “mercies begin afresh each morning.” That’s because he knew exactly how often we would need them.

– Gordy McDonald

Recent Comments